“Beef or pasta?”

“Yes please.”

“Sir, which one – beef or pasta?”

“Uhum.”

“Sir, you have to make a choice.”

The steward was sitting on his haunches, reaching for the trays in the back of the lower levels of the cart. They have a strict timetable and he was getting impatient. The guy sitting next to me was smiling and nodding, oblivious to the question or the context. It was now all up to me – charade the hell out of this one baby! OK, in a split second: how do you charade pasta? No, that way lies perdition. Beef. Easy enough, and if he does not like it, he can signal the other one, whatever the other choice might be – pasta, chicken, snake, but at least he’ll know it’s not beef.

“[making a horn sign on my head] Mooooo.”

“[laughing] Please yes.”

“[Relieved] Thanks. Beef or pasta?”

“Moooo.”

First time in Tashkent. First time in Uzbekistan. First time in Central Asia.

For most Iranians “Tashkent” and “Uzbekistan” are exotic but somewhat abstract. Mention “Samarkand” or “Bukhara”, and suddenly there is a sense of wonder and kinship: eyes open wide; the mind reaches deep into childhood memories of romantic poems and heroic tales. Most Iranians – at least, those with a passing sense of their history and literature – have some sense of these legendary cities, their landscape, and its majestic rivers, even if it is inchoate, distant, wrapped in myth and mystery. The ties that bind the Persianate to these jewels of the Steppes go back 2500 years, through tragedy and sublime poetry and art. And here I was, in the tomb of Tamerlane (part of the tragedy) marvelling at the craft of the Persian (Isfahani) architect who designed and built it 600 years ago (part of the art).

But I am running ahead of myself.

2021 was a year of sadness and of transition.

Early in the year, I lost my grandmother, in part to complications from COVID. She had had a long (102) and fruitful life; for all the challenges of the pandemic, her children saw her before she passed away. I wish I had been there, to say goodbye to her, and to support my mother in her loss. COVID also claimed a cousin. The year ended with the passing of a beloved aunt in Iran; I wish I could have been in Canada, to support my father in his loss.

As with many others in this, the Age of the Pandemic, I also embarked on a new professional adventure. Having finished a really interesting WTO case (the subject matter, the client, and the fact that I argued the case in French), the second half of the year saw me launch an independent consultancy. Although of course risky, this has given me the flexibility to seek and accept projects outside the normal framework of a US law firm. This is how I found myself travelling to Tashkent as the year came to a close and right before Omicron re-upended the world.

Tashkent is a city of broad boulevards, elegant roundabouts, and Swiss drivers. (More than once, with some trepidation we stepped onto the zebra-crossing of the six-lane streets, and each time the cars stopped, hazard lights flashing. When my taxi dared cross a zebra-crossing while a pedestrian was still on it, the police stopped him immediately ….) While there, we were working very closely with Uzbek officials from different government ministries; all of our interlocutors, without exception, were professional, highly trained, and hospitable – the local food was exceptionally good and elements of it reminded me of my days in Iran.

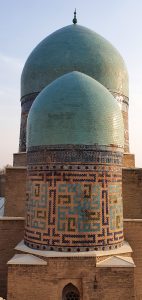

After a week of meetings and presentations and shaking hands and exchanging business cards, we took the fast train (“Afrosiyob”) to Samarkand. It took about two hours to go from the well-ordered boulevards of the new capital to the relative chaos of a Central Asian city, and from the gleaming government buildings to the turquoise domes and minarets of an ancient capital.

The singular claim to fame of Samarkand these days is that it was the seat of Tamerlane, or Amir Teimour, the XIV c. conqueror adopted by Uzbekistan as its national hero.

Iran has a deeply conflicted relationship with Teimour, and with the Steppes, and the visit to Teimour’s tomb was an interesting exercise in cultural and historical translation. To understand the reason why, we need to go back a few centuries.

In the XIII century and under the Khwarazm dynasty, Iran and the Persianate were thriving – independent, unified, connected to and connecting the East and the West through a network of trade routes and magnificent cities, with universities and scientific centres creating and propagating knowledge, and, by then, a 350‑year tradition of Persian poetry culturally linking the Persianate together from the Oxus to the Tigris, from Samarkand to the gates of Baghdad. Well, it couldn’t last, of course. Sultan Mohammad Khwarazmi attacked a Mongol caravan and killed Genghis’s ambassadors, and what followed does not need further elaboration. Only that Genghis spared the province of Fars, the home of Iran’s greatest romantic and social poets, Hafiz and Sa’di.

Fast forward a century and change, Teimour launches his career of conquest, ravages and plunders Iran, and this time, Fars is not spared. What’s more, although Genghis’s grandson eventually established himself in Iran and started something of a building project, and although Teimour’s successors eventually landed in India and established a strong empire there, he and they had nothing to do with Iran’s later recovery (in the 1500s under the Safavids). This is why, in Iran, Teimour has the distinction of having a worse reputation than Genghis.

And so I stood in his mausoleum, listening to the guide telling us about Teimour’s glorious conquests, his piety, his respect for his teachers (his burial place is literally at the foot of that of his teacher), and his love for his main wife (there is a whole complex built in her memory), my mind wandered to loftier subjects – the uses, misuses, and abuses of history.

Or, I should say, the relevance – indeed, the centrality – of perspective. For, Teimour to Uzbekistan is as Nader Shah to Iran; there are statues of Nader littered all over the country. And Teimour to Iran (as I stood in front of the map of his conquests) is as Nader Shah is to India: his biggest claim to fame is of course the plunder of the Moghul treasury of Delhi (along with the slaughter of hundreds of thousands) that led to the collapse of the Empire and the rise of the East India Company. And so it was that when I joked about Teimour’s utter devastation of the Iranian civilisation, the guide reminded me that at least Teimour rebuilt and beautified Samarkand – Genghis did not leave any cities behind, only rubble and ashes and rotting corpses.

There is that.

Samarkand’s monuments were built by Iranian architects Teimour brought back with him from Isfahan and Shiraz; in the bazars, I spoke Persian to the merchants. It felt like home. I mean, I even have a cousin named Teimour.

Somewhere in our excursions someone asked how old the city was. The guide mentioned that Cyrus the Great, the founder of the Persian Empire, had visited the city. I recalled Herodotus: yes, Cyrus had been here, but as a corpse, after his army was ambushed by Tomyris, the Queen of the Massagetae. All in all, we have a complex relationship with our neighbours and cultural kin.

Back to Tashkent, and a late evening walk to a local café where I ordered star-anise tea (I hate anise) and had an indifferent Napoleon (there are better ones in Geneva – and in Toronto), but the atmosphere was delightful and the fact of being there, in a café late in the evening in Uzbekistan, was a cultural experience all on its own.

It reminded me of my first night there: we had decided to stay in the hotel for dinner, and ordered basic hotel fare. That’s how ended up with Tiramisu. In Tashkent. Next time, I know better.